By: Lauren Culler, Research Assistant Professor in the Environmental Studies Program at Dartmouth College and JSEP co-Principal Investigator, and Lee McDavid, Program Manager of the Institute of Arctic Studies, Dartmouth College

Twenty high school students from Greenland, Denmark, and the U.S. learned about polar science this past summer as they gained first-hand experience of how international research teams work together and some of the challenges they face, especially when speaking different languages.

The Joint Science Education Project (JSEP) is co-sponsored by the U.S. National Science Foundation and Naalakkersuisut (Government of Greenland). Established in 2007 during the International Polar Year by the Joint Committee, a high-level forum of the Greenlandic, Danish, and American governments, JSEP is designed to inspire the next generation of polar scientists by giving young students the opportunity to learn in one of most important research locations in the world.

In 2017, JSEP brought together twenty high school students, eight educators and five Dartmouth College graduate students for three weeks of inquiry-based and hands-on polar science in Greenland—a vast ice-covered island ringed by graceful tundra. The students hailed from California, Virginia, Missouri, Massachusetts, Oregon; Copenhagen; and Greenland's four high schools in Nuuk, Sisimiut, Ilulissat, and Qaqortoq. They were joined by a U.S. high school science teacher, Erica Wallstrom from Rutland, Vermont, and educators from Greenland, Denmark, and Chile.

"Most people think that Greenland is 100% covered in ice," says Neosha Narayanan, one of the U.S. students. "My friends are surprised to hear that Greenland is habitable at all."

The first stop for the multicultural and multilingual JSEP team was two weeks in Kangerlussuaq, a community in southwest Greenland that, although small in population, has been supporting international scientific research in Greenland for decades. Students were able get a close-up view of important field sites, including the massive Russell Glacier, Point 660 at the edge of the ice sheet, and Sea Tomato Lake, site of mysterious baseball-sized cyanobacteria.

Students worked in groups to complete projects relevant to Greenland's rapidly changing environment and motivated by questions such as, "how do warming temperature affect permafrost?" Teachers challenged students to experience and understand the scientific process—how to ask a good question and propose a hypothesis, and how to collect and analyze data.

"The projects are one of the best parts of the program," says Melissa DeSiervo, an ecology graduate student. "The students really enjoy working in the field and designing and executing their own project."

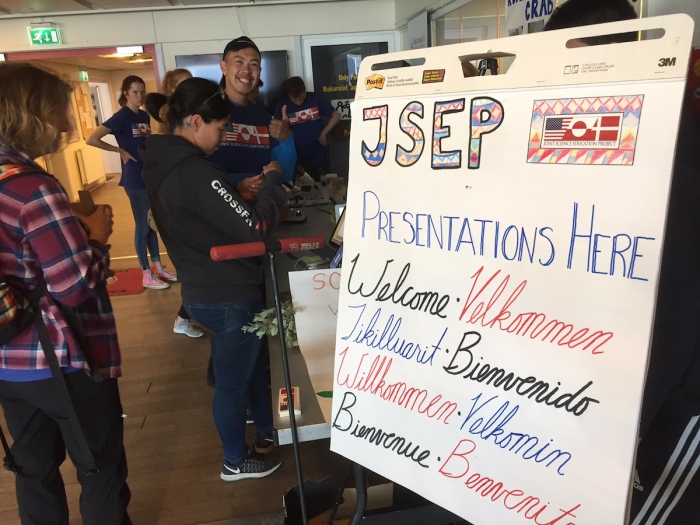

The culmination of their work in Kangerlussuaq was celebrated during an outreach event at the Kangerlussuaq Airport, where students showed videos they had created and talked with international travelers about the significance of their science projects for Greenland, the Arctic, and the world.

"I loved doing the science experiments!" says Neosha. "It was rewarding to present our final research video at the Kangerlussuaq airport afterwards. Our research group definitely bonded a lot during the few days that we had to formulate our research question, collect data, record data, and create our video."

During the third week of the expedition, all twenty students and their teachers boarded a LC-130 cargo plane with ski-equipped landing gear. Their destination was snow-covered Summit Camp, a U.S. research base atop the Greenland Ice Sheet at over 10,000 feet in elevation and an average July temperature of 12˚ F. This year-round facility provides crucial information for understanding Earth's climate. Students learned from researchers about ice and snow and the challenges of doing science in such a remote and frigid environment.

For three years, JSEP has been integrating U.S. graduate students into the core curriculum. This year, five Dartmouth graduate students in earth sciences, biology, and engineering added their expertise, acting as teachers and mentors. The graduate students are also learning—practicing how to effectively communicate science to non-scientists and others not in their area of expertise, a critical skill when working in interdisciplinary and international teams.

"JSEP is a formative experience for graduate students who will increasingly engage with public audiences," says Hunter Snyder, an ecology graduate student. "It fosters a cultural understanding, a crucial part of making science that we can all care about."

The graduate students are also producing polar science lesson plans based on Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) for high school classrooms. A sample lesson plan is "The World of Lichens". With the help of Dartmouth's Institute of Arctic Studies, the host institution for the U.S. contributions to JSEP, the lesson plans will be made available to any school free of charge.

One goal of JSEP is building a diverse international network of students, scientists, teachers, and other stakeholders who understand the necessity of collaboration and educating the next generation of scientists and engineers. "It's awesome to watch the students transform over the course of the program," observes DeSiervo. "When they go back to their schools and hometowns, they are real leaders and Arctic science ambassadors in their communities."

Further information is available on the JSEP website.