By: Melissa Ward Jones, Department of Geography at McGill University

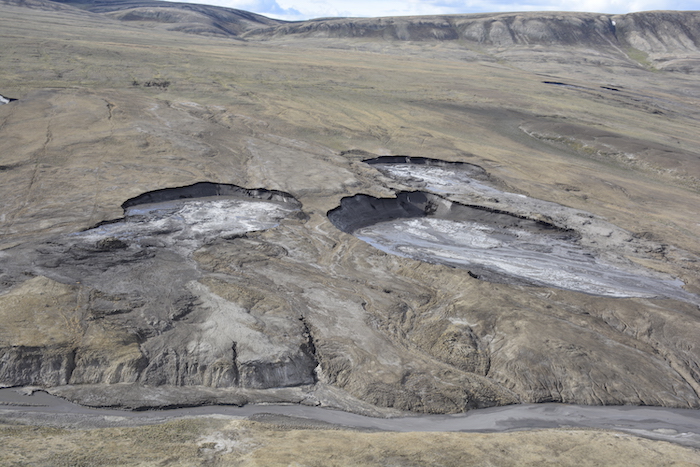

Scanning Canada's high Arctic landscape below us, we perform the same annual helicopter transect of the Eureka Sound Lowlands that Wayne Pollard, Professor at McGill University, has done since 1989 and I have done since 2014. We are looking for active retrogressive thaw slumps (RTS) (Figure 1). These landforms are signs of permafrost instability and form when ice-rich permafrost degrades. They are shaped like a horseshoe and gradually retreat as the ice in the permafrost melts and displaces sediments downslope into rivers, lakes, and the ocean.

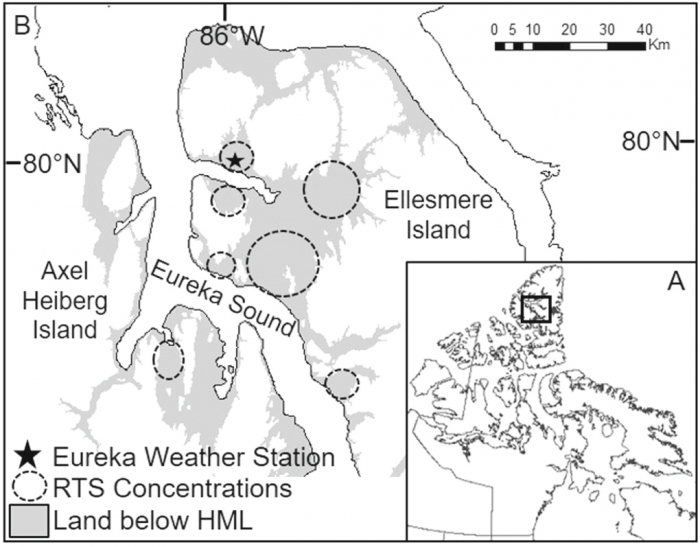

Our research area, at 80°N latitude, encompasses west-central Ellesmere Island (Figure 2) and south-eastern Axel Heiberg Island, Canada's two northernmost islands. The region is a polar desert with patchy vegetation and extensive areas of bare soil. Permafrost here is over 500 meters thick and ice-rich in the upper 20—30 meters. (Pollard, 2000). The ground temperature at about 15.4 meters (the depth no longer impacted by air temperature fluctuations at the ground surface) is -16.5 °C (2.3 °F) and mean annual air temperature is -19.7 °C (-3.5 °F) (Pollard et al., 2015).

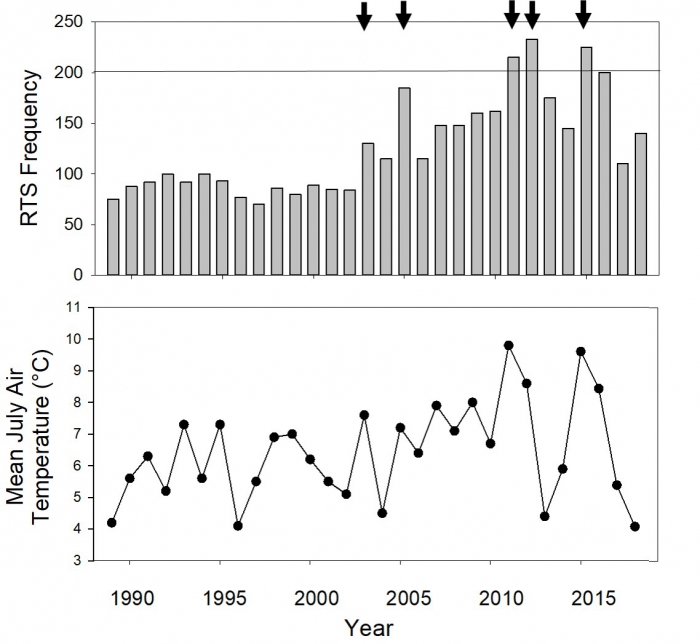

Thaw slumps are not new to this area. These landforms commonly form from local processes such as gully erosion, slope processes, and surface cover changes. However, widespread and rapid increases in slump numbers are indicative of something happening at a larger regional scale. Between 1989 and 2002, active slump counts ranged between 70 (1997) and 100 (1994); after 2003, slump counts ranged between 110 (2017) and 233 (2012; Figure 4).

The highest slump counts of 233, 225, and 215 occurred in 2011, 2015, and 2012 respectively. The three warmest July temperatures recorded by the Eureka Weather Station, of 9.8 °C (49.6 °F), 9.6 °C (49.3 °F) and 8.6 °C (47.5 °F), also occurred in these years (the Eureka Weather Station began record keeping in 1947). Permafrost in the Eureka Sound Lowlands lacks the vegetation and organic surface cover protection that buffers air temperatures, as is found in permafrost areas in the lower Arctic and sub-Arctic. Therefore, this landscape is sensitive to small increases in summer air temperatures.

Our study highlights some important differences in slump dynamics between the high Arctic and the low Arctic (Ward Jones et al., 2019). It, along with a recent study by Lewkowicz et al. (2019), indicates that increases in summer air temperature are driving permafrost degradation. However, studies in the low Arctic have linked increases in slump activity with increased levels of precipitation (Kokelj et al., 2015). Being a polar desert, precipitation is negligible in our study area and daily monitoring of slumps have shown precipitation generates no increase in slump activity (Ward Jones and Pollard, 2018). Accounting for these differences is crucial to accurately estimate pan-Arctic changes and also highlights the complex nature of permafrost responses in different settings. The same landform is being changed by different mechanisms in different parts of the Arctic. Therefore, field observations and studies should be as spatially distributed as possible to account for these differences.

By combining field observations with high resolution remote sensing we were able to reconstruct annual variability in slump growth. I mapped 12 slumps around the Eureka Weather Station between 2014 and 2018 (Figure 5) and with the help of co-author Benjamin Jones (Research Professor, University of Alaska Fairbanks), we extended these observations by including high resolution satellite imagery. With our annual observations we show that, although climate-initiated, terrain factors such as slope may become more important over time in determining slump activity and retreat rates. This further highlights the complexity of permafrost responses.

Our study highlights the sensitivity of this landscape at 80°N and adds to the growing body of literature tracking widespread degradation of ice-rich permafrost (e.g., Liljedahl et al. 2016; Kokelj et al. 2017; Lewkowicz and Way 2019). Not only is degrading ice-rich permafrost problematic for infrastructure, but it also drives changes in vegetation communities (Lantz et al. 2009; Thienpont, et al. 2013; Cray and Pollard, 2015) and slumps release large amounts of sediments and solutes that impact terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems (Kokelj and Lewkowicz, 1999; Mesquita et al. 2010; Kokelj et al. 2013; Malone et al. 2013). Therefore, their impact on a landscape can be profound.

To read this study in full, please see "Rapid initialization of retrogressive thaw slumps in the Canadian high Arctic and their response to climate and terrain factors"(https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab12fd) in the focus on Indicators of Arctic Environmental Variability and Change special issue of Environmental Research Letters.

References

Cray, H. A. and Pollard, W. H. (2015). Vegetation recovery patterns following permafrost disturbance in a Low Arctic setting: case study of Herschel Island, Yukon, Canada. Arctic, antarctic, and alpine research, 47(1), 99—113.

Kokelj, S. V., Lacelle, D., Lantz, T. C., Tunnicliffe, J., Malone, L., Clark, I. D., and Chin, K. S. (2013). Thawing of massive ground ice in mega slumps drives increases in stream sediment and solute flux across a range of watershed scales. Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, 118(2), 681—692.

Kokelj, S. V., Lantz, T. C., Tunnicliffe, J., Segal, R., & Lacelle, D. (2017). Climate-driven thaw of permafrost preserved glacial landscapes, northwestern Canada. Geology, 45(4), 371—374.

Kokelj, S. V., and Lewkowicz, A. G. (1999). Salinization of permafrost terrain due to natural geomorphic disturbance, Fosheim Peninsula, Ellesmere Island. Arctic, 372—385.

Kokelj, S. V., Tunnicliffe, J., Lacelle, D., Lantz, T. C., Chin, K. S., & Fraser, R. (2015). Increased precipitation drives mega slump development and destabilization of ice-rich permafrost terrain, northwestern Canada. Global and Planetary Change, 129, 56—68.

Lantz, T. C., Kokelj, S. V., Gergel, S. E., and Henry, G. H. (2009). Relative impacts of disturbance and temperature: persistent changes in microenvironment and vegetation in retrogressive thaw slumps. Global Change Biology, 15(7), 1664—1675.

Lewkowicz, A. G., and Way, R. G. 2019 Extremes of summer climate trigger thousands of thermokarst landslides in a High Arctic environment. Nature communications, 10(1), 1329. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09314-7

Liljedahl, A.K., Boike, J., Daanen, R.P., Fedorov, A.N., Frost, G.V., Grosse, G., Hinzman, L.D., Iijma, Y., Jorgenson, J.C., Matveyeva, N. and Necsoiu, M., 2016. Pan-Arctic ice-wedge degradation in warming permafrost and its influence on tundra hydrology. Nature Geoscience, 9(4), p.312.

Malone, L., Lacelle, D., Kokelj, S., and Clark, I. D. (2013). Impacts of hillslope thaw slumps on the geochemistry of permafrost catchments (Stony Creek watershed, NWT, Canada). Chemical Geology, 356, 38—49.

Mesquita, P. S., Wrona, F. J., and Prowse, T. D. (2010). Effects of retrogressive permafrost thaw slumping on sediment chemistry and submerged macrophytes in Arctic tundra lakes. Freshwater Biology, 55(11), 2347—2358.

Pollard, W.H. (2000). Distribution and characterization of ground ice on Fosheim Peninsula, Ellesmere Island, Nunavut; in Environmental Response to Climate Change in the Canadian High Arctic, Garneau, M (ed.); Alt, B T (ed.). Geological Survey of Canada, Bulletin 529, p. 207-233, https://doi.org/10.4095/211959

Pollard, W., Ward, M., and Becker, M. (2015). The Eureka Sound lowlands: an ice-rich permafrost landscape in transition. In GeoQuebec 2015 – the 68th Canadian Geotechnical Conference and the 7th Canadian Permafrost Conference Proceedings.

Thienpont, J. R., Rühland, K. M., Pisaric, M. F., Kokelj, S. V., Kimpe, L. E., Blais, J. M., and Smol, J. P. (2013). Biological responses to permafrost thaw slumping in Canadian Arctic lakes. Freshwater Biology, 58(2), 337—353.

Ward Jones, M. K., and Pollard, W. H. (2018) Daily Monitoring of a Retrogressive Thaw Slump on the Fosheim Peninsula, Ellesmere Island, Nunavut. European Conference on Permafrost (EUCOP) Chamonix-Mont-Blanc.

About the Author

Melissa Ward Jones is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography at McGill University, in Montreal, Canada. She is a geomorphologist and her research interests include combining multiple methods to study the nonlinear responses of past, present and future permafrost landscapes to change. She has conducted fieldwork on Axel Heiberg, and Ellesmere Islands, Canada; Svalbard, Norway and Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow), USA.

Melissa Ward Jones is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Geography at McGill University, in Montreal, Canada. She is a geomorphologist and her research interests include combining multiple methods to study the nonlinear responses of past, present and future permafrost landscapes to change. She has conducted fieldwork on Axel Heiberg, and Ellesmere Islands, Canada; Svalbard, Norway and Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow), USA.