By: Sveta Yamin-Pasternak, University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF); Christina Edwin, Community-Based Partner; Marina Koonooka, Community-Based Partner; Jake Pogrebinsky, Community-Based Partner; and Igor Pasternak, UAF

The time of COVID-19 has been highly restrictive for the ethnographic field research, including the socio-cultural study of the pandemic itself. Yet, among those at other recent conferences, numerous exchanges at the 2021 International Congress of Arctic Social Sciences and the annual meeting of the Alaska Anthropological Association show that the Arctic research community has been prompt and prolific in documenting the pandemic-era experiences in the Circumpolar North.

Ours is one of such efforts. Around mid-March 2020, when the quarantining and social distancing measures were first being introduced, we began paying attention to how they were being translated across the diverse cultural landscape of Alaska. We were particularly interested in how quarantining and social distancing would be lived out day-to-day in Alaska’s Indigenous communities, where the widely shared ethos is, “there is no such thing as living alone,” and where all major rites of passage and most everyday practices connected with food, childcare, eldercare, education, and spirituality are guided by the values of inclusion, collaboration, and cooperation. Such traditional care networks involve not only individuals living in close proximity to one another, but also people living in different communities, located far apart, with the members of a network representing both rural and urban Alaska.

As collaborators on the NSF-funded project, Mobilization of Rural Alaska Cultural and Community Resources during the COVID-19 Pandemic, we each contribute in the following roles:

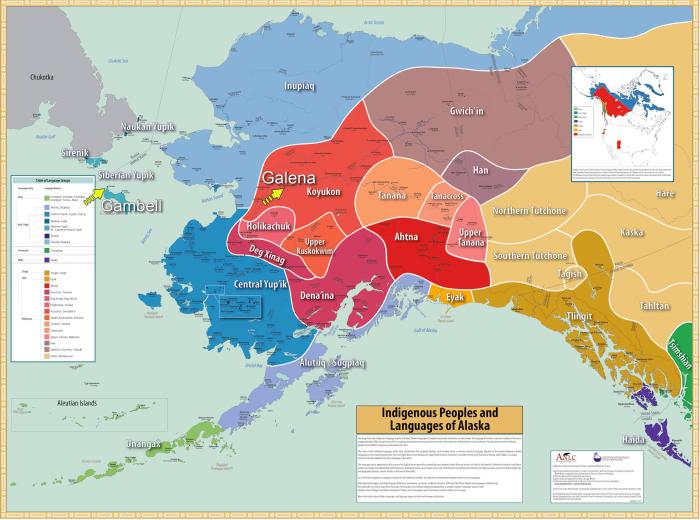

Marina Koonooka is a local coordinator in Gambell, Alaska, a coastal Siberian Yupik community located on St. Lawrence Island in the region of the Bering Strait.

Jake Pogrebinsky is a local coordinator in Galena, Alaska, a community located in the middle-Yukon River region that is the Koyukon Athabascan Dene land.

Christina Edwin is a community organizer involved in numerous initiatives dedicated to cultural vitality and youth wellness. As a caregiver, over the period of the pandemic she has had to travel between Anchorage and the middle-Yukon River region to help members of younger and older generations of her family.

Sveta Yamin-Pasternak is a cultural anthropologist with a long-standing interest in the foodways and cultural expression in the Arctic (see Yamin-Pasternak et al. 2017, 2014).; She is based at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and is serving as the project Principal Investigator (PI).

Igor Pasternak is a broadly practicing artist, educator, and scholar, with long-standing interest in the aesthetics of social and cultural practices in our project’s study regions (Kazmierski 2019); he is based at the University of Alaska Fairbanks and is serving as the project Co-PI.

Facilitated through partnerships between university-based and community-based researchers, our ongoing endeavor utilizes the means of patchwork ethnography (Günel et al. 2020)—an approach that welcomes diverse tools and sources of insight, while relying on longtime commitments and deep contextual knowledge for the interpretation and dynamic emergence of the directions for further inquiry. About 16 months into this effort, we are able to relate chronologies of the pandemic along a range of trajectories. Among those are:

- The local mitigation strategies implemented over the duration of the pandemic in Galena and Gambell and the community-level support given to families and individuals affected during the periodic appearance;

- Community-level support given to individuals and families during the advent of active Covid-19 cases;

- The vaccine rollout (despite the remoteness of the communities and challenges posed by weather and travel conditions, both Galena and Gambell were remarkably efficient at achieving some of the highest vaccination rates in the state by early 2021);

- Harvesting and culinary practices considered essential for the local ways of life;

- Adjustments made in the course of family and community celebrations (including such major life events as graduations, weddings, and funerals);

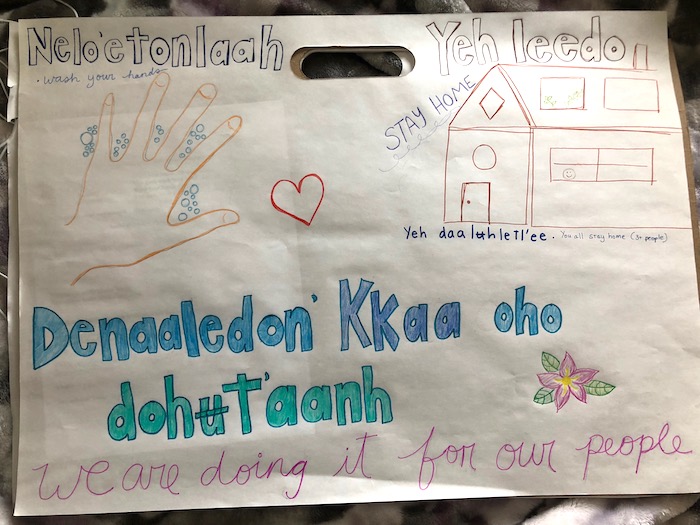

- Roles of traditional performances and newer and older forms of visual art in attending to personal and community wellness, and as a means of documenting and reacting to the experiences of the pandemic;

- Regional and urban-rural connectivity between communities in Alaska; and

- Online community organizing activities, such as the meetings of the Fireweed Collective for the Indigenous Youth and the Denaakk’e language group led by Christina.

The outcomes of this effort continue to be open-ended. At this stage, we believe our work-in-progress warrants a reflection on some prominent ideas, relevant for the pandemic-era social sciences research. At a time when societal discourse, arising amidst the tensions over the strategies and reasons for the mitigation of the spread of COVID-19 around the US and elsewhere, reveals a wide-scale desensitization and apathy toward the susceptibility of the elderly, the Alaska communities’ prioritization toward maximally protecting the elders stands in stark contrast to the phenomenon of “gerocide—the willed mass death of persons deemed old” (Cohen 2020). All the while, the models of community cohesion, efficiency, and resourcefulness being mobilized by groups and networks at our study sites echo the seminal critique of the concept of vulnerability (Marino and Faas 2020) and render into the actions to help promote safety and wellness across generations that our patchwork ethnography is seeking to document and understand.

Acknowledgements

This article presents on the research that is being carried out in the ancestral lands of the Indigenous People of Alaska, and is possible thanks to all of the contributors who have shared their knowledge, experience, and perspectives with the authors. This research is funded through Award# 2035404 from the National Science Foundation Arctic Social Sciences Program, which also provides outstanding mentoring support to the aspiring and active researchers, through the dedicated efforts of its current and former directors, Drs. Erica Hill and Anna Kerttula de Echave. We also gratefully acknowledge the institutional support of the University of Alaska Fairbanks Department of Anthropology and Institute of Northern Engineering; we are especially indebted to Joan Welc-LePain and Crystal Mailloux for the assistance in developing and managing our project.

References

Günel, G., S. Varma, and C. Watanabe. 2020. A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography. Member Voices, Fieldsights, June 9. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-manifesto-for-patchwork-ethnography, accessed August 15, 2021.

Cohen, L. 2020 Culling: Pandemic, Gerocide, and Generational Affect. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 34(4): 542–560.

Kazmierski, K. 2019. Nome Museum Exhibit Embraces New and Old Native Food Traditions, KNOM-Nome, August 15 https://www.knba.org/post/nome-museum-exhibit-embraces-new-and-old-nati…, accessed August 15, 2021.

Krauss, M., G. Holton, J. Kerr, and C.T. West. 2011. Indigenous Peoples and Languages of Alaska. Fairbanks and Anchorage: Alaska Native Language Center and UAA Institute of Social and Economic Research.

Online: https://www.uaf.edu/anla/map, accessed August 15, 2021.

Marino, E. and A.J. Faas. 2020. Is Vulnerability an Outdated Concept? After Subjects and Spaces. Annals of Anthropological Practice 44(1):33-46.

Yamin-Pasternak, S., P. Schweitzer, I. Pasternak, A. Kliskey, and L. Alessa. 2017. A Cup of Tundra: Ethnography of Thirst and Water in the Bering Strait. In Meanings and Values of Water in Russian Culture. Jane Costlow and Arja Rosenholm (eds.). Pp.117–136. Routledge.

Yamin-Pasternak, S., A. Kliskey, L. Alessa, I. Pasternak, and P. Schweitzer. 2014. The Rotten Renaissance in the Bering Strait: Loving, Loathing, and Washing the Smell of Foods with a (Re)Acquired taste. Current Anthropology 55(5):619–645.

About the Lead Author

Yamin-Pasternak is a cultural anthropologist who studies how foodways in northern communities interact with the local climate, built environment, family and community relations, ecology, and aesthetics. She collaborates with researchers across the fields of social and natural sciences, Indigenous scholarship, humanities, and engineering. She is also a world-leading researcher in the field of ethnomycology.